He’s really dead. She’s really a he. He is his mother’s killer. She is her sister’s mother. All of them did it. No one gets out alive.

And then there’s the all-time favorite surprise ending: It was only a dream. Or a nightmare.

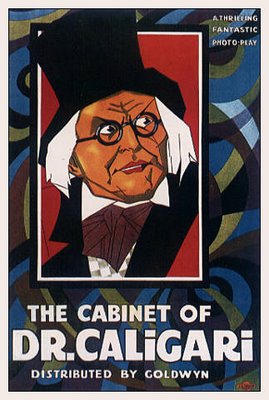

You can trace the latter trick all the way back to the dawn of the silent-movie era, and follow its various permutations even beyond the audacious turnabout that signaled Bobby Ewing’s return to Dallas. But when you’re cataloguing the most significant cinematic deceptions, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari deserves special mention. This 1920 German fantasia represents the first meaningful attempt to fuse Expressionistic style and conventional substance in a commercial film. Just as important, however, is the movie’s seminal success at pulling the rug out from under its audience.

Indeed, even the people who wrote it claimed they were surprised by what happens in its final scene.

Caligari begins prosaically enough, with handsome Francis (Friedrich Feher), seated next to a stranger on a park bench, promising to tell a stranger about an adventure he shared with Jane (Lil Dagover) – his beautiful fiancée, who just happens to be passing by -- in their small German town of Holstenwall.

Once Francis begins his tale, however, the film shifts into a phantasmagorical fantasyland, as characters go through their paces in an Expressionistic universe of distorted perspectives, asymmetrical doorways, crooked windows, sloping chimneys -- and streaks of light and shadow painted across tilted walls. Officious bureaucrats sit atop enormously high stools, frowning down upon fawning supplicants. Sleepwalkers stagger across impossibly slanting rooftops, and through forebodingly twisted forests.

Take note of the many angled shapes and pointed objects that, right from the start, are sprinkled throughout the film. (Visual allusions, perhaps, to the dagger wielded lethally in key scenes?) These sharp geometric figures convey a pervading sense of danger and evil, serving as exceptionally potent portents in a movie teeming with scenery that often threatens to chew up the actors.

(In his audio essay for the film’s DVD release, scholar Mike Budd persuasively argues that Caligari was the first moving picture to introduce Expressionism to the masses, and movies to Europe’s intellectual elite. On the other hand, critic Pauline Kael was no less persuasive when she noted that, while Caligari is “one of the most famous films of all time” and “a radical advance in film technique,” the German masterpiece “is rarely imitated -- and you’ll know why.”)

Against this bizarre backdrop, director Robert Wiene unfolds a comparatively mundane horror story about Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss in outlandish make-up and Mickey Mouse gloves), a sideshow charlatan who causes murder and mayhem in Holstenwall with the help of his star attraction, a somnambulist named Cesare (Conrad Veidt, who would later cause trouble for Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca).

These prototypical bogeymen – cinematic templates for succeeding generations of manipulative mad scientists and, more recently, Halloween-style indestructible death-dealers -- are perfectly in sync with the stylized make-up and scenic design. At least, that’s the view espoused by film historian Lotte H. Eisner in The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt (1952). Insisting that the “characters of Caligari and Cesare conform to Expressionist conception,” Eisner elaborates: “The somnambulist, detached from his everyday ambience, deprived of all individuality, an abstract creature, kills without motive or logic. And his master, the mysterious Dr. Caligari, who lacks the merest shadow of human scruple, acts with the criminal insensibility and defiance of conventional morality which the Expressionists exalted.”

Cesare -- whose unnaturally white face, heavily mascaraed eyes and black-on-black wardrobe suggest a Goth-influenced bit player from Night of the Living Dead, or a first draft of Edward Scissorhands – pops out of Dr. Caligari’s cabinet to answer audience questions during a fairground show. Unfortunately, Francis and Alan (Hans Heinrich), Francis’ friendly rival for Jane’s affections, are among the curious onlookers when Cesare makes his Holstenwall debut. Even more unfortunately, Alan asks an imprudent question (“How long have I to live?”) and gets an immediate answer: “Until tomorrow’s dawn…”

Sure enough, Alan comes to an untimely end shortly after staying too long at the fair. Francis, no fool, figures things might not be on the up-and-up with the good doctor and his black-clad accomplice. So he returns to the fairground, only to glimpse a heartwarming tableau: Dr. Caligari, fawning over Cesare like a kindly mother, feeding broth to his charge in the privacy of their caravan. Hardly anything incriminating, Francis figures. More to the point, with Alan out of the picture, Francis now has exclusive dating rights to the beautiful Jane.

As the body count mounts in Holstenwall, however, Francis feels compelled to avenge his late friend -- and, naturally, protect his beloved Jane – by joining the local police in a hunt for whoever’s behind the killing spree. The clues lead to Cesare, and beyond him to Caligari. The trail ends at an insane asylum, where Caligari is revealed as not merely a patient, but rather the deeply disturbed director of the institution.

But then, just when it looks like everyone – except Cesare and Dr. Caligari, of course – will live happily ever after, the movie opens a trapdoor: The entire melodrama is the product of Frances’ fevered imagination. In the final scene, we discover the nominal hero is in fact a delusional patient in a loony bin operated by a benevolent Director who looks just like – ta-dah! – the malevolent Dr. Caligari. “At last,” the Director exclaims, “I understand the nature of his madness. He thinks I am that mystic Caligari. Now I see how he can be brought back to sanity again…” Authority is validated, order is restored.

In 1920, this climactic twist stunned audiences – and infuriated the film’s screenwriters.

Austrian scenarist Carl Mayer and Czech poet Hans Janowitz originally conceived Caligari as a cautionary allegory aimed at audiences still recovering from the ravages of World War I. As far as they were concerned, Caligari personified an unlimited state authority that idolizes power, while Cesare represented, in Janowitz’s words, “the common man who, under the pressure of military service, is drilled to kill and be killed.” When Francis unmasks Caligari, his triumph shows that – again, in Janowitz’s words – “reason overpowers unreasonable power.”

Trouble was, neither director Wiene nor producer Erich Pommer felt altogether comfortable with the ramifications of the original script. They feared retaliation by any powerful people who might interpret the allegory as a personal attack. More important, they worried that audiences would respond unfavorably to anything that reminded them, even indirectly, of the everyday horrors lurking just outside the movie theater.

You see, during the 1919-1933 heyday of the Weimar Republic, a period now widely recognized as a golden age for German cinema, many of the filmmakers’ countrymen felt they were living a wide-awake nightmare. A sudden spurt of inflation could impoverish almost anyone in a matter of weeks, if not days. Women and children were driven to prostitution, often with the tacit approval of their needy families. Street brawls between Communists and National Socialists occurred frequently enough to qualify as spectator sports. The grand experiment in postwar democracy simply wasn’t working. Or, perhaps more accurately, wasn’t allowed to work.

Much like audiences in Depression-ravaged America, Weimar-era Germans sought escape from harsh realities by seeking escapism at the movies. Historical romances, costume dramas and lavish epics based on ancient legends were prime box-office attractions. Equally popular, however, were dramas of the macabre and fantastical – tales of horror, phantasms and science fiction – that allowed audiences a safe way to savor catharsis through the playing out of worst-case scenarios.

At such a time, in such a place, folks might like to exorcise their worst well-founded fears by enjoying a scary melodrama about a modern-day wizard and his murderous cat’s-paw. What folks most assuredly wouldn’t like, Wiene and Pommer decided, was a movie that could inspire “dangerously radical” notions about government and the governed.

Which is why, despite fervent protestations by Mayer and Janowitz, the allegorical nightmare was transformed into a striking but safely apolitical dreamscape. Specifically, Wiene and Pommer – aided by filmmaker Fritz Lang (M, Metropolis), who freely offered detailed script suggestions, and had originally considered directing Caligari himself – contrived the device of wraparound scenes that identify Francis as a paranoid fantasist.

With the invaluable collaboration of production designers Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann and Walter Rohrig, Wiene offers in Caligari a boldly stylized rendering of “reality” as viewed through the eyes of a madman. And if the director undercuts his own “explanation” by depicting the supposedly “real” reality of the opening and closing scenes in the same unrealistic manner, well, chalk it up to Wiene’s compulsive showmanship.

But consider this: A decade or so after the 1920 premiere of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Adolf Hitler underscored the prescience of Mayer and Janowitz by demonstrating just how easily a mesmerist could cloud the minds of the masses. As German film historian Siegfried Kracauer notes in his aptly titled From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film (1947), the Expressionistic silent classic “is a very specific premonition, in the sense that (Dr. Caligari) uses hypnotic power to force his will upon his tool – a technique foreshadowing, in content and purpose, that manipulation of the soul which Hitler was the first to practice on a gigantic scale.”

Thereby proving, alas, that the scariest nightmares are those from which you cannot awaken.